The following is a version of Carolane De Palmas, a shopping analyzer at Retail FX and CFDS Broker Activetrades.

At a time when most advanced economies continue to fight persistent inflation, Switzerland is in the opposite state: consumer prices are just increasing and, at times, even shrink. This scene has revived the speculation that the Swiss National Bank (SNB) could be forced to review one of its most controversial policy tools – negative interest rates.

The debate was intensified after June 2025, when SNB cut the policy rate for the sixth time in the current relaxation cycle, bringing it up to 0%. This move marked a turning point, asking the question of whether the zero rates, which were abandoned just three years ago, could return as a weapon against persistent frustration and a growing Swiss franc.

Negative prices reverse the traditional logic of funding on her head: instead of interest -earning lenders, borrowers are paid effectively to receive loans, while commercial banks are charged to own excessive stocks at the Central Bank. For Switzerland, the measure has long served a dual purpose -lending and spending at home, while limiting the relentless assessment of the franc, which threatens exporters and inflation below the 2% SNB stability target.

Why did Switzerland introduce negative prices in 2015?

Switzerland chose negative interest rates in December 2014 as a way of dealing with the threat of deflation and a dangerously powerful franc. When prices fall firmly throughout the economy, people and businesses are delaying costs waiting for even lower prices ahead. This can cause a downward spiral of weak demand, shrinking profits, job losses and slower growth. By highlighting rates below zero, the Swiss National Bank hopes to discourage the accumulation of cash and instead encourage households and businesses to borrow, spend and investing.

The move was also an answer to the repetitive periods of Switzerland’s deflation. Consumer prices have been immersed in negative territory several times in the last decade: from 2011 to 2013, again between 2014 and 2016, and more recently during the pandemic between March 2020 and March 2021. In fact, inflation was negative for about one third of all months since 2009. Previous year, stressing how fragile inflation remains. If the basic rates remain at 0%, SNB provides inflation to reach 0.2% in 2025, 0.5% in 2026 and 0.7% in 2027.

Why will Switzerland consider re -reduce its basic percentages below zero?

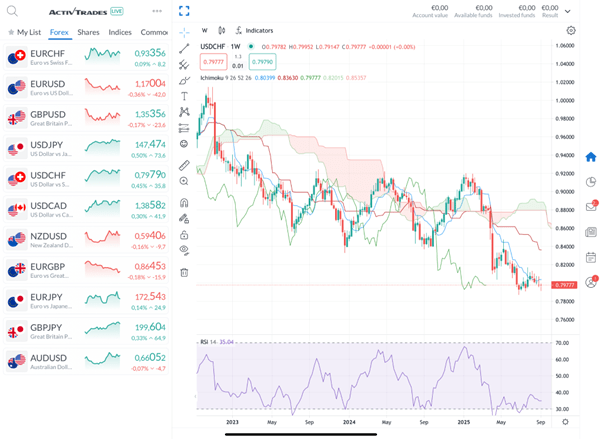

The debate over whether Switzerland could return to negative interest rates has reappeared in 2025, mainly due to its emergency power Swiss franc. The currency has risen to the highest level than the US dollar since 2011, gaining almost 12% since the beginning of the year. Against the euro, Franc has estimated more than 15% since March 2021 and over 21% since March 2018. This relentless rise has maintained inflation close to the weak levels of years, raising questions about the Swiss National Bank’s ability to respond to the stability mandate.

Weekly USD/CHF – Source: Activtrader

A powerful franc makes imported goods cheaper, household pillows and businesses against the increase in domestic expenditure. While this may sound like good news for consumers, it is in danger of undermining the SNB’s goal of maintaining inflation close to 2%, the level that is considered to be in accordance with healthy, sustainable development. In recent months, inflation has rolled just above zero, with consumer prices increasing only 0.2% on an annual basis in August. Such supposed price pressures intensify the speculation that SNB can be forced to act again, possibly rejuvenating the negative rates as a tool for dealing with the currency with the currency.

SNB President Martin Schlegel warned that while the Central Bank is ready to combat low inflation with tools such as currency interventions or returning to negative prices, he is also aware of the disadvantages. He notes that the last era of sub-dimensional interest rates caused significant pain for savings, banks and pension funds.

For the time being, markets are expecting SNB to keep prices unchanged at the next policy meeting on September 25, especially because inflation remained within its scope for three consecutive months. Analysts argue that policy -makers are likely to remain careful in view of increased global uncertainty – including the Washington decision to impose 39% invoices on Swiss imports. Still, officials were careful to emphasize that all options remain on the table, reflecting the dangers of ongoing monetary assessment and fragile prospects.

The story adds weight to the current discussion. Switzerland became the first major economy to introduce deep negative interest rates in 2015.

Bond markets indicate that investors are already staggering for the policy of politics. Officials in short -term Swiss government bonds have fallen below zero, with two -year yields of about -0.11% in early September, having reached a three -year low -0.25% in June. Such moves indicate that financial markets see negative prices as more than just a theoretical choice – they can become reality again if inflationary pressures further weaken and the franc refuses to soften.

How can negative rates affect the Swiss economy?

By paying banks to maintain excessive stocks to the Swiss National Bank, policy -makers are aimed at providing lending and investment rather than saving. But while the theoretical transmission channels are clear, the practical consequences were more complicated – and in some cases problematic – for the Swiss economy.

From a theoretical point of view, negative values work through many channels. First, they reduce the cost of borrowing, encouraging households and businesses to spend and investing. Secondly, they weaken the domestic currency, making Swiss assets less attractive to foreign investors, which helps exporters. Finally, they promote investors to the risk curve, away from safe assets, such as government bonds and in shares or real estate, stimulating activity in these areas.

However, in practice, Switzerland has experienced significant side effects:

- Savings and pension funds: Households earn little or no return to bank deposits and in some cases face dot charges to maintain big balance. The pension funds-hands depend on government bonds and low-risk securities-they set long-term liabilities, as yields are pushed deeper into negative territory. This undermines the security of retirement and raises questions about justice between generations.

- Banks and financial stability: Commercial banks can see their net interest margins compressed, as the gap between what they earn on loans and what they pay for deposits is shrinking. To maintain profitability, many have turned to the market for mortgages, helping to increase lending and boosting Swiss real estate prices to record high levels. The SNB itself has repeatedly warned of overheating of housing risks and the potential accumulation of economic imbalances.

- Companies and investment behavior: While borrowing costs are historically low, companies facing global uncertainty – they belong to commercial tensions and, more recently, geopolitical disorders – often prefer to sit in cash rather than expanding investment. This emphasizes a theoretical paradox of negative rates: cheaper credit does not necessarily guarantee higher investment if trust is missing.

Sources: Ing Think, Investopedia, SNB, Reuters, Wall Street Journal